WHAT IS CHANGING, WHY?, HOW?, WHERE?, WHEN? WHAT IS REASON FOR CHANGE?, LIKELY RESULT OF CHANGE? GOOD? BAD? CAN WE (CITIZENS) CHANGE CHANGE? STOP CHANGE? REDIRECT CHANGE? SLOW/SPEED CHANGE? CAN WE DEAL WITH IT AND STILL HAVE FUN?

Friday, June 12, 2015

Thursday, June 11, 2015

Amsterdam Will Put New Housing on 10 Artificial Islands - CityLab

Amsterdam's Bold Housing Solution: 10 Artificial Islands

To create the islands, the Dutch use a technique called the “pancake method.”

- FEARGUS O'SULLIVAN

- @FeargusOSull

- 10:57 AM ET

- Comments

Right now, Amsterdam’s Center Island (Centrumeiland in Dutch) doesn’t look like much—just an inhospitable sand bar poking out from the city into the huge IJmeer Lake. But there’s far more to it than meets the eye at present. The island, in use for the first time this summer as a campsite-cum-art installation, is in fact an entirely artificial creation, lying at the heart of what could currently be Europe’s boldest engineering and housing program. This sand bar will become one of 10 new residential islands rising from the depths of the IJmeer. In a distinctively Dutch move, Amsterdam is not only planning for future expansion by building a network of model neighborhoods to expand into—it has actually constructed the ground on which those neighborhoods will stand.

Construction of this new archipelago, called the IJburg, began in 1997, and so far six of the total 10 planned islands are complete. To construct the islands, the Dutch used a technique they call the “pancake method.” When an island is built-up this way, porous screens are placed in the water to hold the island’s shape and sand is sprayed into the screens to form a layer of batter-like sludge. As this layer settles and drains through the fine mesh, it hardens and another layer of sand is sprayed on top. Pancake by pancake, the island rises until it is two meters above the water level.

The first six islands built this way are now inhabited, albeit not entirely built-up and populated to their maximum capacity. Residents first moved onto the islands in 2002, and the city’s tram network was extended to them in 2005, bringing what was once a backwater within 15 minute of Amsterdam’s Central Station. The islands have been covered with an attractive mix of low- and medium-rise housing, threaded with self-build plots and some floating homes. While the three main islands contain many mid-rise buildings laid out on urban streets (as you can see here on Street View), the three smaller islets between the main islands and the coasts have a more explicitly suburban character. On the islets, low-rise single-family homes are grouped along the shorelines, which will ultimately be filled in with gardens and reed banks. Each of the six islands is purposely thin in order to maximize water views.

The construction of the archipelago marked a significant departure for Amsterdam. From the 1960s to the 1990s, finding space for the city’s overflow population primarily meant constructing new towns far from the city core. New settlements such as Almere and Lelystad (both also built on reclaimed land) fed the sprawl that has effectively turned all the major cities of the Netherlands into a single conurbation. By constructing the IJburg, Amsterdam took a new direction. The land is still reclaimed, but it is far closer to the city’s historic center. Instead of treating Amsterdam as complete and starting again elsewhere, the IJburg plan has managed to find more space in a city that thought it had no more left.

The gradual construction of the final four islands—a project called IJburg II—is finally due to begin after a few years of zoning wrangles that stalled full development on Center Island, leaving it as a bare promontory. What the city of Amsterdam calls a “start vision” (essentially a loose blueprint) was agreed to on March 24 of this year.

The last pancake of sand needs to fully settle before Center Island is ready for building, but construction of between 1,000 and 1,200 new homes should begin in 2017. Three other islets called Outer, Middle, and Beach Islands (Buiteneiland, Middeneiland, and Strandeiland in Dutch) are also planned. Should Center Island prove successful, they will emerge soon after in the open waters beyond. If you look on Google Maps, you’ll see their names already there, hovering eerily over the water. When fully complete, the archipelago will be home to a population of up to 45,000 people in 18,000 homes, 30 percentof which will be earmarked for affordable rent.

That pause between phases of constructing the IJburg islands was arguably beneficial because it allowed some key concerns about the program to be heard. Most of these focused on the IJmeer Lake itself. A vital habitat for birds, it’s a wide-open space that a crowded, densely built-up country like the Netherlands can ill afford to spoil. The lake is a place of austere but unmistakable beauty—arriving suddenly at its banks and seeing its great sweep out in front of you is one of the scenic highlights of the Netherlands. If handled poorly, building further along its banks could scare off the birds, disrupt the waters, and ruin the views. The pancake method itself can also be a problem, as it was with the earlier islands. According to Cobouw, a publication about construction, during bad weather, the screens holding the islands’ shape sometimes ripped and leached sludge onto the lake bottom, requiring repair and threatening mussel beds.

Center Island’s construction should avoid these pitfalls. To give extra protection to the island’s sludge screens by sheltering them from the current, a 600-meter breakwater has been constructed to the east of the island site. And following the input of the public from a year-long consultation at theAmsterdam Architecture Center, the future islands will probably be leafier and more low-rise than initially envisaged, each with a band of green around their fringe to preserve lake views. The new islands will also be energy self-sufficient. Developers are entertaining the idea of rooftop solar cells and district heating to achieve this goal, in addition to giving more space to self-builders. Based on experience from the IJburg’s earlier islands, self-builders are more likely to install well-insulated, eco-friendly heating and wastewater systems.

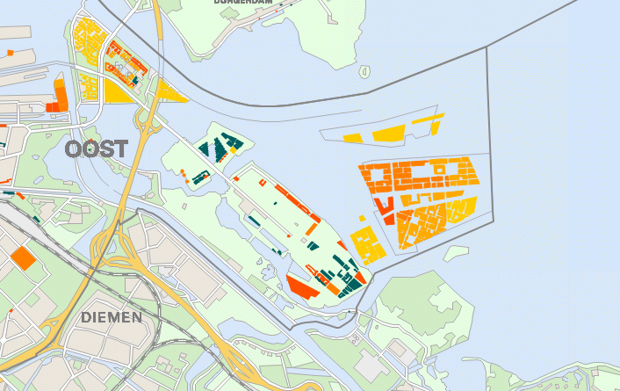

None of this is likely to happen that fast. The Amsterdam housing plan projections shown in this map reveal that parts of the new islands will likely not be constructed until after 2026. That needn’t be a drawback. The refinement of the whole IJburg project over time shows the benefits of gradual development in engaging the public and improving the end product. After all, if you’re going to create a city neighborhood out of what was once just a stretch of open water, it pays to take your time.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)